If you’ve ever been to the theater, you’ve seen them — the comedy and tragedy masks. These familiar laughing and crying faces pop up everywhere, staring up at you from playbills and acting company logos. The next time you see them, consider this: the drama masks have been a symbol of the theater for more than 2,500 years!

It all started in the city of Athens in the year 535 BC. The city had just built the first theater in the world — the iconic Theater of Dionysus. As the first actors stepped on stage that April afternoon, they were wearing masks. Contrary to popular belief, these masks didn’t communicate emotion; rather, they represented different characters in the play. (Kind of like supersized Halloween masks.)

Today, we have just two masks: happy and sad. In ancient Greece, there were 44 different types of masks for comedy plays alone!

Photo: Andreas Praefcke, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Masks were so familiar to audiences that they started to appear in other places. Archaeologists have found theater masks on Greek vases, Roman columns, and tiled frescoes. In ancient Athens, artisans carved them into small pieces of bone and ivory to make the first theater tickets.

Drama masks went out of fashion before the fall of the Roman empire — but by then, they were a well-known symbol for the theater. The masks we use today honor the ancient Greeks’ favorite types of plays: comedy and tragedy.

Top image courtesy of Tim Green under CC BY 2.0

What do the comedy and tragedy masks mean?

When used together, the two drama masks are a symbol for the theater. The laughing mask symbolizes comedy, while the crying mask represents tragedy. Modern audiences sometimes ascribe additional meanings: the range of human emotion, for example, or the extremes of the human experience.

What are the two drama masks called?

The tragedy and comedy masks are usually called “Thalia and Melpomene” or “Sock and Buskin”. Although the words come from Greek drama, it’s a modern invention to use them as names for the theater masks — the ancient Greeks and Romans did not start the trend.

Thalia and Melpomene

The names Thalia and Melpomene are references to two of the Greek Muses, the deities who were the source of inspiration for artists and musicians. Melpomene was the Muse of tragedy, and Thalia was the Muse of comedy.

Faqscl, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons, edited for color

Sock and Buskin

“Sock and Buskin” refer to two types of footwear worn by the world’s first actors. Comedic actors wore the soccus, or sock. Low-cut and loose-fitting, this thin-soled shoe was similar to a modern slipper. The soccus tradition started in ancient Greece and continued into Roman times. The Roman playwright Plautus mentions the soccus in his play Epidicus (Act 5, Scene 2).

Tragic actors wore buskins, which were high-heeled boots. The heel made the actor look taller — perfect for the heroic, ideal humans in Greek tragedies. Historians don’t agree on the use of the buskin in the theater. Based on the plays that survive, some argue that it was actually a women’s shoe. In this context, playwrights would have used it to give an effeminate quality to certain male characters, including the god Dionysos.1

Why did ancient Greeks wear masks in theater?

Ancient Greek actors wore masks in the theater because it was a cultural tradition. The first plays evolved from the rituals worshipping the god Dionysos. Since these rituals involved masks, it was only natural that the first actors would also be masked.

The theater masks were practical, too. In ancient Greece, three actors played all of the speaking roles in a play. (the Three-Actor Rule) By changing masks and wigs, they could transform into a new character in seconds. Plus, since women weren’t allowed to be actors, the drama masks enabled men to play female roles.

Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Then, there’s the size of the theater. If you’ve ever been to Greece, you know that ancient theaters were enormous. The Theatre of Dionysus in Athens held between 15,000 and 17,000 people! Masks were larger-than-life and made with exaggerated features, so audiences could identify the characters clearly. Some researchers also believe that the mouth openings acted like megaphones, amplifying actors’ voices.

Color was also important, especially for the people sitting in the back row. Greek artists at the time often used dark skin for men and light skin for women — to help the audience distinguish between characters, the masks followed the same convention.2

Are there any surviving Greek theater masks?

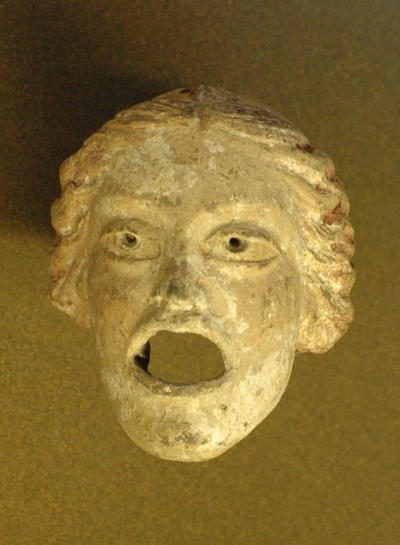

There are no surviving Greek theater masks. That’s because each mask was made from materials like stiffened linen, wood, and leather; these materials degrade quickly, so they’re lost to the centuries.

How do we know what the Greek theater masks looked like if none survived?

Archaeologists have found pottery and terracotta miniatures in Greece that show what drama masks looked like. The ancient Greeks painted theater scenes onto vases — hundreds of these pieces survive, giving us a clear picture of the masks in action. In the second photo below, you can see how the mask is considerably larger than the actor’s face.

CristianChirita, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

According to Edith Hall, a professor of classics at King’s College London, these vases are a rare opportunity to see actors in costume.

History of the drama masks

Dave & Margie Hill / Kleerup, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The comedy and tragedy masks originate in ancient Greek theaters. Instead of wearing stage makeup, like we do today, actors wore a different mask for every type of character.

If you were attending a tragic play in Athens in the year 500 BC, you might see a female mask with dark hair and a thin face. You’d know instantly that this female character was a good Athenian woman with high morals. On the other hand, if the actor was wearing a female mask with a round face, red hair swept into a tall updo, and a wreath of ivy, you’d know she was a courtesan — an upper-class prostitute.3

Louvre Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Since the character masks were so recognizable, theatergoers knew exactly how to feel about each character — and what to expect in terms of behavior. Playwrights took this opportunity to surprise audiences. The good Athenian girl might do something devious, for example, while the courtesan might be a “hooker with a heart of gold”. (A trope that still lives on in movies like Pretty Woman.)

Those are just two examples — in his Onomasticon IV, Greek historian Julius Pollux described 44 different character masks in New Comedy plays, as well as 28 for tragedies.4

Comedy and tragedy masks in ancient Greek theater

The two drama masks come from the two types of plays that were common in ancient Greece: tragedies and comedies. The masks appeared in the Lenaia and the City Dionysia, two huge Athenian festivals celebrating Dionysos, the god of wine.

Theater competitions were a big part of the festivals — three tragedians went head to head with plays written just for the occasion, and a panel of judges picked the winner. In 486 BC, the festivals officially added a separate contest for comic plays. All of the actors were masked.

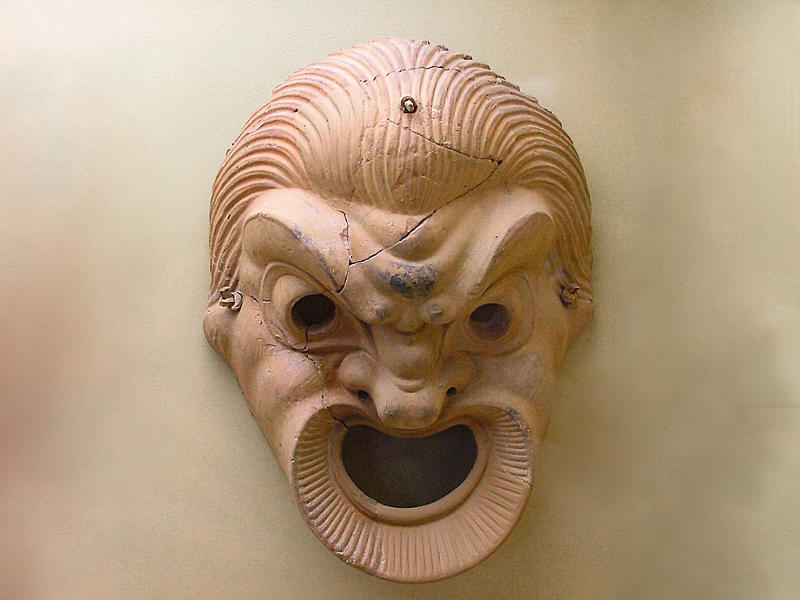

Tragedy masks were beautiful and heroic, with idealized features. They were used in plays by men like Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides, who wrote about stories in Greek mythology. Greek tragedies were serious and rich in moral lessons.

In contrast, early comedy masks were often cartoonish portrayals of gods and famous citizens of Athens, according to Professor Edith Hall in a lecture at Gresham College. The masks — and the plays themselves — insulted and mocked these prominent people. They delighted the now-drunk audiences with sharp political and social commentary.

“Nobody was immune. They talked freely about sleaze, corruption, and personal toilet habits,” said Professor Hall. “…The intensity of abuse characters suffered in comic theater ensured that only robust, popular, and clever men could survive to be reelected.”

Dorieo, Wikimedia Commons (License CC-BY-SA 4.0).

Even as these Old Comedy plays gave way to the more nuanced New Comedy plays, the Greeks continued to use a similar style of masks. As Rome started to conquer parts of the Greek world, this tradition continued.

Masks in ancient Roman theater

As Rome began its rise to power, Roman playwrights borrowed many of the ancient Greek traditions. Writers like Plautus were heavily influenced by the Greek Old Comedy and New Comedy. In Rome, theater masks were more crude, particularly in comedy plays.

Between the years 212 BC and 173 BC, mimes started to become a popular part of Roman theater. Mimes didn’t wear masks, and as audiences got used to seeing actors’ facial expressions, drama masks fell out of favor.4 Bawdy Roman theatergoers preferred the salacious subject matter of mime performances (adultery was a favorite) to the serious historic tragedies.

Masks reappeared in the theater when the art of mime evolved into the pantomime during the first century AD. In a pantomime, the lead character didn’t speak — instead, he wore a mask and danced the action. A big, singing chorus provided the music. Sound familiar? That’s because modern musicals and ballet both have roots in ancient Roman pantomime.

Over time, masks disappeared entirely from the Roman theater. They remained an important symbol, however, decorating buildings and works of art for centuries to come. The comedy and tragedy theme has been reinterpreted and simplified, evolving into the laughing and crying masks we know today. Modern versions pop up in a range of cultural settings, including the series Family Guy.

Citations

[1] Smith, Kendall K. Harvard Studies in Classical Philology. Department of the Classics, Harvard Unviersity, 1905, pp. 123-164.

[2] Sinclair, Andrea. “Unmasking Ancient Colour; Colour and the Classical Theatre Mask.” Ancient Planet Online Journal, vol. 4, 2014, pp. 42-61.

[3] Green, Richard, Eric Handley. Images of the Greek Theater. University of Texas Press, 1995.

[4] Bieber, Margarete. The History of Greek and Roman Theater. Princeton University Press, 1961.